Abstract

Reading a research paper can be daunting and time consuming. Whether the goal is to find a topic one is interested in pursuing, reading sources in support of an ongoing project, or reading a review of a certain topic, a paper’s structure is relatively the same. Therefore, this strategy of reading a research paper can be followed with any peer-reviewed, published article. It focuses on reading the main points of a paper to first assure that the reader will gain desired information, and then on how to learn from a paper that may introduce topics the reader has never encountered. The tips are formatted much in the same way as a scientific paper to introduce readers to a research article.

Introduction

Research is an important component of education. It connects what is learned in the classroom to real applications. Unfortunately, there is no structured class on how to conduct a research project.1 A foundation of knowledge built on the work of others is necessary to expand upon areas that have yet to be explored. This is, of course, offered in a lecture class setting, but often does not go into the details necessary for focusing on one specific project. More specific background information must be gleaned from other researchers’ works.

There are many reasons to read a paper.2 Any person that intends to read and gain information from a research paper is themselves a researcher. The researcher could be trying to:

(1) more fully understand a topic

(2) form a new hypothesis

(3) find data and resources to support a new project

(4) edit and review another researcher’s work 3

All these goals can be reached by following the guidelines herein.

Most research papers are structured similarly to the outline of this paper.2,3,4 They begin with an abstract, which is more like a conclusion in its focus on what the most important aspects of the paper are. The abstract is a short synopsis of the major topic and findings of the paper. The introduction expands upon the abstract and poses why the research conducted should interest the reader.2,4 It is often the longest section, but also the easiest to understand. It is important that the introduction be accessible because it will make the reader want to finish the paper to understand what was gained by the research project. Following the introduction is the methods section (in most cases, some article structures place the methods at the end), which outlines how the research was carried out. It should be in enough detail that someone could repeat the study with the same results, which is the mark of a good paper. This leads into the results, which is where the data analysis is provided. There are often many figures and tables for the reader to decipher. Most of the analysis and impacts on the project’s goals are detailed in the discussion and/or conclusion section(s). This is often referenced when a researcher is deciding whether to use a paper’s findings in their own research.

In undergraduate and graduate courses, the emphasis of research papers is often placed on the proper way to write a paper. This can help orient oneself on what an author considers when writing, but it does nothing to elucidate what their research means or how it pertains to greater applications. It is important to have an entirely different strategy when reading a paper than when writing one.

Methods

The methods of reading a research paper detailed below are provided as a framework. It is up to the reader and the purpose of reading as to how in-depth the reading will be. There is no timeline on how long this process will take and some papers are easier to understand than others.4 It is also necessary to go into more detail when reading a paper in a field one is less familiar with. However, following the guidelines will provide a technique that if employed will become second-nature to the reader and very important in their career as a researcher.

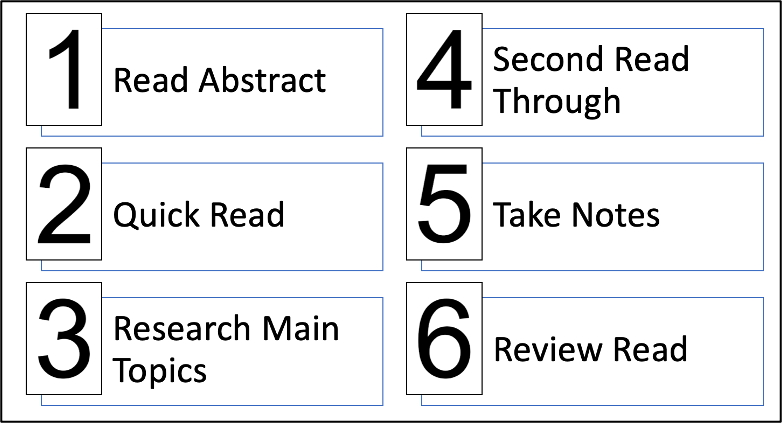

- Read the abstract2 – Try to pick out the main focus of the paper and the results that it contributes to the topic. This precursory read will allow the reader to determine if the paper fits within the scope of their research and/or if they are interested in learning more of what the paper has to offer.

- Read the paper once through – This may feel like reading a book in another language.1 Don’t get stuck trying to understand every detail. This shouldn’t be the read where you absorb every word and meaning, you are merely observing someone else’s work.

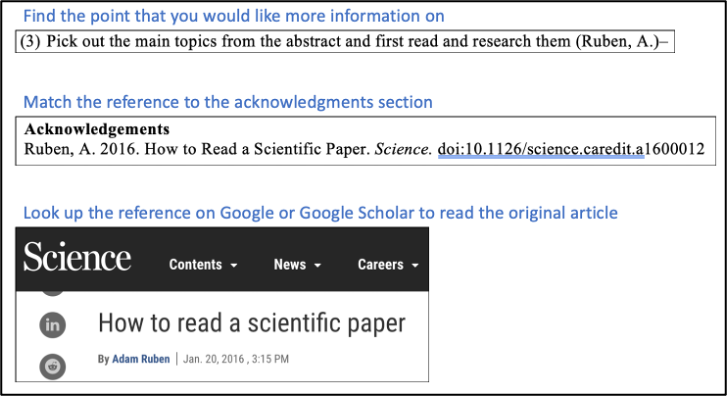

- Pick out the main topics from the abstract and first read and research them1 – This is the time to use Google. Finding other peer-reviewed papers is less important than finding information that you can more fully understand. This will help you relate back to what you just read. Once you can put the main points of the article into context, it will help you focus on the details and learn more in the next read through.

- Start the second read through – Start going back through the paper and defining words, phrases, terms, acronyms, etc. that you may not have understood. It is important to use Google again, or Google Scholar especially in the use of acronyms. Read excerpts of other papers if this helps to contextualize terms, but don’t get lost or distracted by new content. The most useful way to learn more details about something in the paper that is unfamiliar is to refer to the author’s list of references. The author will list a reference that provided them more detail on a topic right after it is written in their paper. Oftentimes, the term or topic they are using is followed by the reference number that can be located in the acknowledgements section.

- Take copious notes of the author’s progression5 – The author’s thought process can be teased out of the methods and results sections. If the reader can understand how the research project progressed, then it is easier to understand the topic. Figures are your friend because they visualize the important thoughts that may not come across at first in writing. (Disclaimer: don’t focus too much on data analysis unless you are editing the paper). See the reference Hewitt, J. for strategies of close note-taking.

- Read the paper a final time – Now that you have defined terms, taken notes, and seen the material twice, this read through should feel like a review. Focus on the things that the author points out as still unknown and relate them to your research and/or how you could contribute to this topic.

Results

The overall goal of close-reading a research paper is to understand more about the topic than before. Rather than reading an article at face value, it causes the reader to understand the author’s approach to the topic and the thought process of the research.1 This will not only aid in gaining knowledge about an area of interest, but also in strategies that the reader can employ or questions that they can ask within their own research pursuits.

When researching a topic that could lead to a new project, it is important to apply the close reading techniques when first familiarizing oneself with the information. After reading a paper in depth and taking copious notes, reading subsequent papers on the same topic will come more easily. The reader can refer back to notes and definitions from the first paper, and also note similarities and references that authors share in their research. This will help the reader frame the papers they read in the broader spectrum of the research topic, and also to navigate where their research will fit.

Another outcome of employing these reading techniques is that the process will become easier with time and practice. Reading in this way, while time consuming, can make the material less daunting. If the research topic is more approachable, than more people will be able to understand and learn from it. This will not only lead to an increase in the sharing of knowledge within the research community, but also in the accessibility of knowledge to the public. The internet age has made learning so easy and accessible, but it has also increased the amount of difficult information being neglected for short, and often misleading articles. Becoming a researcher is to truly understand a topic, but to also be able to scrutinize it and compare it to other works to maintain the integrity of the topic. Anyone can be a researcher when they want to learn more, but like any skill it takes knowledge and practice to find the right information from a research paper.

Discussion

Reading and writing strategies such as the one detailed in the methods section are meant as a guideline to practice and adjust to each researcher’s needs. The format of this article allows for exposure to the structure of a research paper. As extra practice, try to use to techniques outlined to review this paper once again. This should store more information from the paper itself and prevent the need to go back and forth between reading strategies and the paper being analyzed.

The next step is to employ these reading strategies to another scientific paper. Read through any paper of choice and try to recall the most important details. Then, employ the reading strategies and repeat the exercise. Adjust the strategies to fit individual needs until the information is easily recalled. This will make research and learning more effective and rewarding.

Undergraduate research projects expose students to applications of topics learned in the classroom. Laboratory techniques, data analytics, computation, and other skills are taught and practiced through mentors and faculty. Reading is a skill that is expected by all researchers. However, the transition from reading books to research papers is difficult, and it is easy to get lost in unfamiliar terms and explanations. With practice and time, every researcher can learn the skill of approaching a paper, learning the most important points it has to offer, and applying newfound knowledge to their research.

References

- Ruben, A. How to Read a Scientific Paper. 2016. doi:10.1126/science.caredit.a1600012

- Little, J. and Parker, R. How to Read a Scientific Paper: Biochemistry/MCB 568. http://www.cs.swarthmore.edu/~newhall/cs97/s00/ReadingAdvice.html. May 2020.

- Durbin, C.G. How to Read a Scientific Research Paper. Respiratory Care. 54, 1366-1371.

- Branson R.D. Anatomy of a research paper. Respiratory Care. 49, 1222-1228.

- Hewitt, J. and Purugganan, M. How to Read a Scientific Article. Rice University.